Monday 20 Nov: DAY 4 OF RECOVERY

I wake up at my usual early hour of about 6am having had patchy but bearable sleep on night three in hospital. To be honest, I’ve been having patchy but bearable sleep since my son was born sixteen years ago and the perimenopause segued nicely a few years later, so, whether I’m in hospital recovering from a mastectomy or at home after a quiet night on the sofa watching Amandaland, patchy but bearable sleep isn’t really newsworthy. Let’s move on!

I open my eyes to the cityscape I will never tire of and get ready for the morning drill that I’m used to by now; lots of staff coming in and out with yellow name badges monitoring my progress, topping up water jugs, bringing my medication, removing plates, checking blood pressure, checking my left breast. It’s the usual hive of activity.

Following yesterday’s first tentative steps out of bed and with the catheter now removed I must make my way down the corridor to use the loo. Having been told about the importance of mobilising I brace myself for that little journey. Once again I have to do a painstaking manoeuvre to get myself off the mattress and lower myself to the floor. It’s slow. It’s steady. I still feel as though I’m going to split in half if I straighten my back but I do it anyway knowing that I need to ‘un-hunch’.

I put on my slippers, (those freebie towelling ones you get in hotels or spas), gather up the drain attached to my left breast and place it in the bag I was advised to bring for this purpose - (it means you don’t have to wander round clutching a container of your blood and bodily fluids in much the same way you would clutch a takeaway coffee cup). Fun.

Drains: Out of sight = (more) out of mind + it’s more practical to have a spare hand. Off I go.

My first solo toilet trip is fine although I could do without the full length mirror positioned bang opposite the toilet seat and the harsh overhead lighting shining down on my new wounds. However I’m aware this is a hospital and not, despite its penthouse views, the Park Plaza hotel just down the road.

It’s in that toilet with its unforgiving striplight that I get to have a really good look at the stitches across my stomach for the first time. I’m intrigued and just a little bit horrified. There’s no getting away from the fact it looks brutal and I can’t help thinking that in decades to come and with medical and technology advances constantly being made, we’ll look back at this kind of surgery and go, ‘They actually used to do that?’

I gently prod my stomach around the long line of stitches and inspect my new belly button hole. The whole area is numb as I’ve been told it will be for months, possibly years.

After my toilet trip I walk around a little bit as advised by the nurses. It feels like an achievement to be out of my room without any assistance for the first time even if I resemble a feeble and frail octogenarian who looks like they could benefit from a walking frame.

I shuffle along the corridor and soon discover I can do circular, (incredibly slow), laps around Somerset Ward. I set myself a target to do three or four and get my first glimpse of other patients who are in adjacent rooms, a mixture of men and women who are all recovering from a wide array of different surgeries. I had previously imagined I would be among other women going through mastectomies and that we might exchange snatches of conversation in some kind of communal area and compare notes. So much for that notion. I don’t speak to a single other patient the whole time I’m in hospital. As I make my way around at the pace of a sedated snail just a couple of doors are ajar. I see a woman who looks my age propped up in bed. Our eyes meet. She acknowledges me with the faintest wisp of a tired and knowing smile.

After a couple of laps, and getting a little more confident with the walking, I decide that's enough moving around for the time being. I slowly return to my room and sit in the chair by the window looking out at the view, my dressing gown draped across my lap for comfort. The Monday tourists are already starting to mill around and I watch the flow of people heading along South Bank where the London Aquarium, The London Eye and The Paddington Bear Experience are all vying for their cash.

I’m watching the clusters of people stopping to pose for selfies on Westminster Bridge when a staff member comes in and hands me some feedback forms to fill out. There are about five or six pages of questions asking me to rate my experience including everything from the level of care, to how the medical staff worked together, to cleanliness, to food.

During your stay were you treated with kindness and understanding?

Yes, always / Yes, sometimes / No / Don’t know. Can’t remember

Do you think hospital staff did everything they could to control your pain?

Yes, always / Yes sometimes / No / I did not have any pain

How would you rate how well the doctors and nurses worked together?

Excellent / Very good / Good / Fair/ Poor

I’m taken aback because it seems premature. I am still here. I am still being treated. It’s like being asked to review a restaurant before your tiramisu has arrived or rate your Uber driver when he’s still five miles from your destination.

However, I soon realise maybe the forms are not so premature because the next person who comes to see me is one of the plastic surgery nurses who I met at the Show and Tell event the previous week.

‘Right, well good news, you can go home later today,’ she says in a chirpy voice.

I’m in shock. This is not ‘good news’ to me. It is worrying and alarming and overwhelming news. I only managed to stand for the first time yesterday. I can barely walk. I still have my drain attached. My catheter was only recently removed.

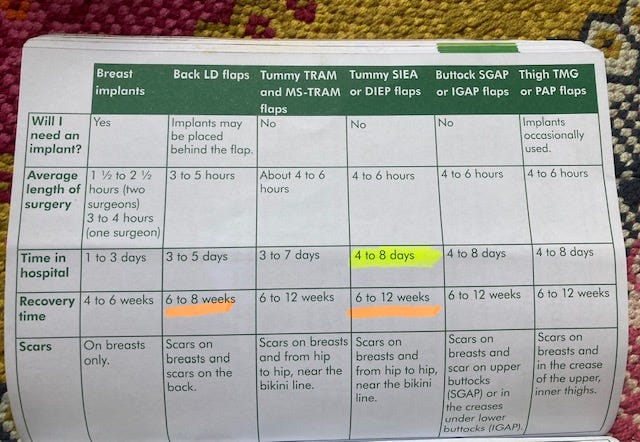

My thoughts loop back to the angry patient I heard outside my room on the first morning telling the staff he’d been sent home too soon and was now back in hospital with further complications. My mind also turns to the recovery section of the Macmillan booklet I was given in preparation weeks before which states that following a DIEP you can expect to be in hospital for four to eight days. This feels like a very abrupt three.

‘I don’t feel at all ready’ I say as my panic levels immediately spike.

‘That’s completely normal’ replies the nurse matter-of-factly. ‘People often think that but you’ll feel much better being in your own bed at home’.

But no. It’s the thought of being in my own bed that is one of the things frightening me. Right now I’m in a bed where I can press a button and it helps tilt me into a helpful position so I can get out of it. I’m on a ward where I don’t have to navigate stairs to get to my bedroom or worry about steps to go to the toilet in the middle of the night. Here in hospital I can press a buzzer if I need assistance or there’s an emergency and someone with medical training who hopefully knows what they’re doing will appear. No disrespect to my partner Jonny, my teenage son or Sammy the cat but I’m not sure any of them would be quite so well equipped if things suddenly took a downward turn once I’m back at home.

The nurse leaves the room. I stare out of the window mulling over how I’m feeling. ‘It’s too soon. It’s too soon’ is the recurring thought looping on auto.

(I made this little video, above, shortly before the tearful floodgates opened later on).

A bit of time passes and then another nurse comes in and introduces herself. I think she is the Ward Sister. I’m not quite sure of her title or role but I soon gauge she’s probably responsible for allocating beds. Her tone is brusque and her opening sentence is, ‘I hear you don’t want to go home today. What’s the problem?’ She is firm, unsmiling, she has a job to do and I totally understand the pressures on bed spaces in hospitals. I try to explain my worries physical and mental. She responds in a stern tone, ‘The longer you stay in hospital, the higher your risk of picking up an infection.’

I don’t know how to react to this. I now feel as though I’m being scared into leaving as quickly as possible. I stay silent. My eyes begin to pool with tears as I stare out of the window unable to react. She leaves the room.

More time passes and the next person to enter is Sebastien, the nurse who gave me my first shower yesterday. She arrives with one of her assistants, a lovely student nurse from Canada who will later explain to me she is on a work placement.

Sebastien busies herself filling a large bowl with soapy warm water intending to give me a bit of a clean, she asks how I’m doing.

It’s at that point that my mouth crinkles and tears start sliding down my cheeks. Before I know it I’m gulping and sobbing. The floodgates have opened.

‘They want me to go home today,’ I splutter trying to gather my breath. ‘But I’m just not ready. It’s not like I’ve just had a hip replacement or heart surgery to fix something ….This is the beginning for me. The mastectomy is just the start…. (sob, sob)… I still don’t know whether I’m having chemo…. (sob sniff) …I’ve still got to go through radiotherapy. I’m in limbo …the tumour has to be sent off for analysis…I don’t know what’s going to show up…I just can’t do this. (sob, gulp) It’s the mental stress, it’s not just the physical side. I only stood up for the first time yesterday, I can barely walk and now I’m supposed to go home?’ I go on in emotional freefall letting my fears and thoughts flood out and pool into the small room as Sebastien listens.

She lays a comforting hand on my arm and tells me not to worry. She says she will go and speak to someone.

More time passes in which at some point I must have eaten lunch. I can’t quite remember the time scale but the next person to come in and speak to me is one of the surgeons from the plastic surgery team. He asks me a few questions, checks over my notes and tells me he’s spoken to the team and understands I am worried about leaving hospital. Is that correct?

I nod my head.

I’m feeling shattered, subdued and scared. He tells me that it is fine. He’s happy to let me stay for another night and we can reassess how I feel in the morning. A huge surge of relief washes over me. My fear and anxiety levels take a drop. I can do this. Tomorrow is manageable. ‘Yes’, I say. ‘Thank you.’

Nurse Sebastien reappears later in the day to do more checks and I realise I have her to thank. She tells me it was her who had spoken to the surgeon and said she didn’t think I was ready.

‘It wasn’t right,’ she says. ‘You need more time.’

She is my hero. I am so grateful to her.

‘Thank you’ I say. ‘Thank you,’ and find my eyes dampening with yet more tears, this time ones of relief and gratitude as I manage to raise a small smile.

As the hours pass I mentally prepare myself. Tomorrow will be a new day. I will get through another night here knowing there is medical support on hand. Tomorrow I will be just a tiny bit stronger. It will be daylight. It will all be ok.

I have since found an extract in Rosamund Dean’s excellent book Reconstruction in which an oncoplastic breast surgeon, Miss Georgette Oni, explains how common it is for a patient to find it difficult to cope emotionally around the two or three day mark. She says, ‘What I have noticed with patients is a couple of days after surgery, they get really, really upset and sad. I call it the ‘day two blues’ and I think it’s because they are getting over their anaesthetic and seeing the reality of what’s happened. It’s very common for the patient to be teary as the gravitas of everything hits them.’

This explains perfectly how I was feeling. I felt knocked off course when I was expected to leave the hospital at the very point I was feeling at my most vulnerable mentally. It was overwhelming. Up until then I had been focusing on the physical side. ‘I’m feeling nauseous post-anaesthetic. Do I need someone to bring me a bowl? I need to stand up. What’s the best way to do that? Can I manage to walk by myself? Let me try.’ As those physical concerns and benchmarks got ticked off so space opened up in my brain making room for thoughts, reflection and a reality check.

It was on day three that it really hit me. Thats when the tears and fears came. ‘I have gone through eight hours of surgery. I have had my nipple permanently removed. I have a disc of skin taken from my stomach in its place. I have no idea if I’ll be having chemotherapy in a few weeks. How will my body tolerate radiotherapy? Did they get all of the tumour out? Am I going to be ok?’

Everyone is different and everyone will have different experiences. I have since spoken to women who stayed in hospital for three nights after their DIEP, four nights, six and seven.We will all react and respond differently no matter how smoothly or not our surgery goes.

I am glad I spoke up and said I wasn’t ready to leave as I strongly believe it ultimately helped aid my recovery in the long term. (More on that later). I am forever grateful to Sebastien that she spoke up for me too. Monday was a day too soon. I felt underprepared, incredibly vulnerable and rushed but by the following morning it was a different story.

Next time: Going home, my first night in my own bed and some tips on how to prepare.

If you have found this post helpful or enjoyed reading it, please do share it, press the little heart button below to like it, (It helps more people find it), restack it or forward to anyone you think might find it useful.

And if you’d like all of my future posts delivered straight to your inbox then consider subscribing and you won’t need to check back here.

Thank you for reading x

Thanks Tess, my mastectomy is next week and your posts have been really informative and helpful, thanks x

A great post! Whilst I skipped the emotional day 3 part I clearly remember the first time I looked in the mirror properly at the hospital (the scary ‘take a shower on your own ‘ day). I sent a message to my husband describing my physical appearance as similar to a squashed pygmy!!