It is Saturday 11 November, 2023. In six days times I will be undergoing major surgery to remove the tumour that has been growing silently and stealthily in my left breast. I am in a room at St Thomas’s hospital, London amid a group of about 18 women I have never met before and a handful of men. We are offered cups of tea and coffee as we arrive by smiley ladies wearing hot-pink T-shirts and ‘Restore’ lanyards who welcome us to lines of plastic chairs that sit facing a screen. There is a gentle hum of talk as strangers politely introduce themselves or sit silently with their loved ones. I recognise one of the nurses standing to the right in her grey uniform. It’s Mariamma. She gives me a reassuring nod.

This time next Friday I will be unconscious in this same building while a team of skilled surgeons, nurses and anaesthetists do their work on me to take out my cancer, perform a mastectomy and rebuild my left breast. The operation is expected to take between seven to eight hours if all goes to plan.

I am 52-years-old and feeling anxious and jittery about what lies ahead. I have lost count of the amount of conversations and routine meetings I have had with medical professionals over the past two months since a surgeon with a flat voice, eyes like hard brown buttons and a business-like manner broke the news that I had Grade 2, oestrogen stimulated, lobular breast cancer and informed me that due to the size of the tumour I would need a mastectomy, my nipple removed and follow up radiotherapy, possibly chemotherapy.

He delivered the news in much the same way as a dour and joyless waiter might inform you that your bank card has been declined as you attempt to pay your bill.

I have leafed through the numerous pamphlets by Breast Cancer Now and Macmillan Cancer Support that kind nurses have gently pressed into my palms as I’ve slipped tearfully out of small, windowless hospital rooms. I have looked at the diagrams and photographs of women’s breasts post-surgery, the nipple reconstructions, the different body shapes, the various options in which facts and explanations are given on the array of treatments and resulting side-effects I can expect to have.

I have poured over books including Reconstruction by Rosamund Dean, Victoria Derbyshire’s diary, Dear Cancer and The Complete Guide to Breast Cancer by Professor Trisha Greenhalgh and Dr Liz O’Riordan, but I have been wavering and deliberating over which procedure I want to go ahead with.

The learning curve has been steep.

Before my diagnosis my knowledge of mastectomies was limited and vague. I pictured flat-chested women, bald from chemo, breasts removed, scars here and there, maybe implants. I had no idea that plastic surgeons could work at the same time as oncology surgeons to do an ‘immediate reconstruction’ using fat taken from other parts of a patient’s body such as the stomach, thighs, back or buttock in order to build a brand-new breast

There are options to consider. Decisions to be made. Research to be done and it’s at times overwhelming. I have met two different plastic surgeons at St Thomas’s both of whom have suggested the best option for me would be the DIEP Flap reconstruction using fat from my stomach to make a new breast. The word ‘flap’ makes me think of loose skin dangling from my torso or a handy access route for a cat. I don’t like it.

DIEP stands for Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator. I have just had to look that up because even now I am unable to remember the acronyms, the words, the new glossary of medical terms that have been thrown my way since a radiographer with a furrowed brow told me she ‘was quite concerned’ about the images from my routine mammogram and subsequent ultrasound. Never before has the word ‘concerned’ made my blood run so cold.

I have been gently and respectfully prodded and poked by two successive plastic surgeons, one female, one male as I’ve stood, dressed in just my M&S knickers as they assess my body. “Yes, you’ve got enough here in the stomach area. The thighs also”, the male surgeon gives a gentle squeeze as he pinches my inner thighs between his fingers.

“Not so much here”, he looks at my bum. I am amazed. Not enough fat in my bum? Who’d have thought. “The stomach area would be best for you”, he concludes.

I glance down at the pouchy skin resting above my knickers, the result of two babies born 15 and 18 years ago, now worried teenagers who are heroically readjusting to the news their mum has cancer.

“It would be like a tummy tuck’, the surgeon continues. This sounds like a positive amid the mire of negatives that have been piling and heaping ever since that fateful diagnosis in August.

“Amazing what they can do these days’, a well-meaning friend will chip in over a coffee when I explain what is possible. ‘Wouldn’t mind a tummy tuck myself! If you need any spare fat I’ll volunteer”, she smiles before leaving bite marks in the generously piled icing atop her carrot cake.

But then there is also the option to have nothing. To be flat. To have a breast reconstruction at a later date or to have a breast implant. Many cancer patients, and seemingly all the female celebrities who have dared to share their cancer treatment stories, opt for implants.

There are pros and cons for all, lists of side effects and possible complications for all. I have see-sawed between decisions. I have even asked the plastic surgeon how late in the day I can change my mind as if I’m choosing a new sofa and want assurances I can switch fabrics and designs at the last minute.

I have at every turn been met with reassurances and helpful information.

Which is why here I am now at the suggestion of Mariamma, one of the lovely nurses in my ‘Cancer Squad’ (my label, not theirs) who, a couple of weeks ago rang me to tell me about the ‘Show and Tell’ event being organised by the charity Restore.

“It’s the first time we’ve held one of these at St Thomas’s”, she explains, “Former mastectomy patients will model their bodies, you’ll be able to chat to them, see the results of the surgery and of course ask them questions. I think you may find it helpful.”

And so here I am. I am chatting to a smiley stranger could Lou Lou who is in the audience next to me. It is hot in this room. We are a room of largely menopausal and peri-menopausal-aged women, many of whom have had to abruptly halt our HRT because of our cancer. Hot-flushes abound. Lou Lou gets out a mini pink handheld fan and nudges it into my palm with a smile. “Here you go, keep it. I’ve got plenty of spares.” She nods towards her handbag.

As we wait for two nurses to manoeuvre a flat screen into place she explains to me she had a double mastectomy thirteen years ago and implants put in. After various surgeries one implant has now sunk and crumpled towards her armpit and needs to be taken out. She will later offer to show me and, my curiosity piqued, I will accept. Which is how we come to find ourselves, an hour after we have met for the first time, huddled in a disabled loo while Lou Lou undoes her bra straps.

She is now on a waiting list for the DIEP Flap reconstruction. It is a surgery I am unsure about having. It is one she is desperately keen to have.

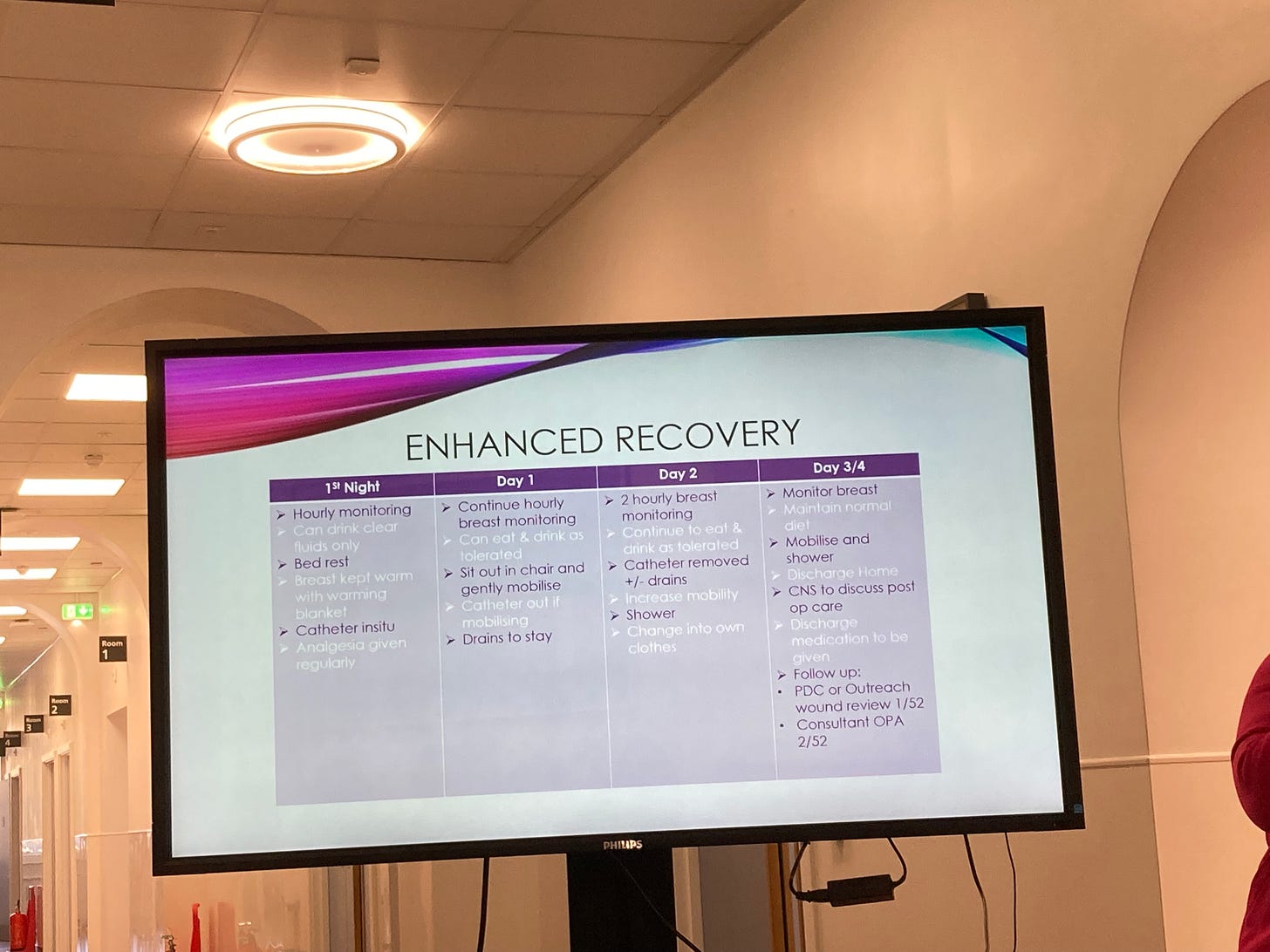

Mariamma introduces herself and fellow nurses, Billie and Kerry to the room which has fallen silent. Over the next 45 minutes Kerry shows us pictures and diagrams on the screen of surgical options and explains the terms and procedures. It is like being in an intriguing Biology lesson in which all of us attending students will at some stage become living exhibits.

The talk is helpful and informative but now it is time for the ‘Show and Tell’ part of the morning. The males in the audience, husbands, partners, friends are ushered into a side room by one of the Restore volunteers while a line of seven women all clad in pink-dressing gowns arrive and take their seats on the row of chairs facing us. They are a mixture of ages, shapes and colours. One by one they take it in turns to stand and tell their own stories, the shock of the diagnosis, the absence of any warning lump, the niggling pain they felt in their right breast on their way back from B&Q, the routine mammogram that bore bad news. Some were diagnosed ten years ago. Others much more recently.

They share their experiences, they talk about their recoveries, they reveal what they wish they’d known and offer their personal insights. And then, one by they drop their gowns to show us their scars, their mastectomies, their reconstructions, their new breasts.

One lady has opted to have a beautiful tattoo of a flower in the place where her nipple once was, its petals and leaves blossoming across her chest. Another turns to show us the scar running across the top of her buttock where fat was taken to make her new breast, another explains how her incredibly life-like nipples are in fact 3D tattoos while another describes the procedure in which her breast skin was twisted, ‘like origami’ to make a new right nipple. One tells us why she had opted to be flat, another reveals why she chose implants rather than the DIEP flap.

A lady with a beaming smile and a fizzing energy tells us how much she ‘loves her new tits’, another praises the bonus of her newly-flat stomach.

We look at the ‘holes’ where new tummy buttons have been made. We are shown ‘dog ears’ where a scar may have puckered. They praise the surgeons who worked on them, the nurses who cared for them. Some say they followed all the post-surgery advice to the letter, diligently doing their physio exercises, others say they couldn’t face it and spent subsequent weeks comfort-eating on the sofa.

They talk about their returns to work, the obstacles that have come their way, the complications and the successes. They are honest. They are inspiring and their bodies tell their stories. The overriding message is one of positivity.

They have done what no book, online diagram or photograph could have done. They have brought the experience of their mastectomies to life and kindly and bravely shared their bodies and words with a room of anxious, overwhelmed, intrigued and scared women who are united by this indiscriminate disease.

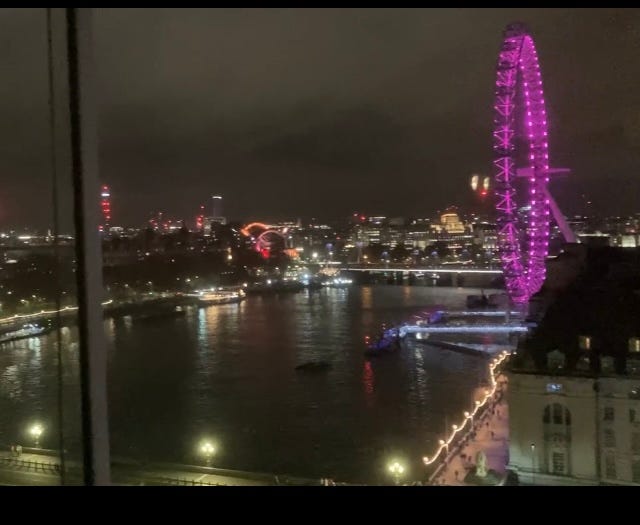

A week later I am lying post-surgery on the twelfth floor of the same hospital as tubes and drains collecting my blood come out of me. It is the dead of night and the glow of the London Eye through my hospital window and the city skyline are my only company. My mastectomy and DIEP flap surgery took eight hours but as I lie dazed and unable to sleep as the dark ripples of the Thames snake before me, I am relieved that the cancer is out of me.

I am scared about my recovery and what the removal of the tumour may show up as it is sent off for further testing and analysis. I don’t know whether I will need chemo. I don’t know lots of things right now. But as I lie on my back unable to move I summon up those seven volunteers in their pink dressing gowns and feel their strength and positivity cocoon me. They all got through this. I can too.

Their generosity in sharing their stories, scars and rebuilt breasts was invaluable. It’s why, six months after my surgery and my recovery which has been smooth and straightforward, I am back at St Thomas’s this time as one of the volunteers.

Here I am now sitting in my Restore-issue pink dressing gown, looking out to the audience in the rows of chairs where I sat six months ago. I can see the fear in some of their faces, some are bald through months of chemo ahead of their surgery, one lady directly in front of me is quietly dabbing her cheeks with a crumpled tissue trying to stem the flow of tears, another is looking down fiddling anxiously with the bag on her lap. Another who heartbreakingly looks to be in her twenties, is listening and watching intently, her eyes wide with concentration.

We are all in this together.

I wait for my turn to stand and show my new left breast, the empty circle where my nipple once was and the sixteen inch scar that runs across my new flat stomach.

I want to tell them all it will all be ok, that they will somehow navigate this hellish path that no-one wants to be on that is littered with potholes and unforeseen landslides but is dappled with rays of hope, comfort and camaraderie.

I want to say, “We got through this. You can too.”

Wow Tess you are amazing. Thank you for sharing 🙏🏼😘

You are a brave & courageous women Tess. ❤️